|

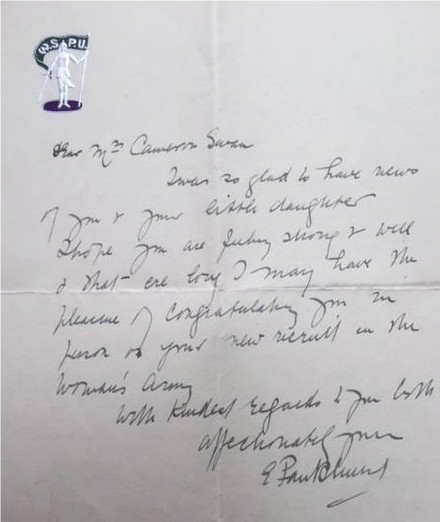

The next woman on the amnesty record is Greta Cameron alias Greta Cameron Swan whose actual name was Grace Cameron Swan. The first report of Grace being active in the suffrage movement is a donation, to the WSPU £20000 fund, of £3 in May 1908. By the following spring, Grace is the secretary of the Croydon Branch of the WSPU; both chairing and addressing meetings. In May, Grace chaired a meeting, in South Norwood, at which Christabel Pankhurst and a campaigner released from prison spoke. As women were arrested and sent to gaol, the WSPU would invite them to meetings after their release, not only to show their appreciation but to learn of their experiences. Few, who attended those meetings, would have been unaware of what, potentially, faced them. Grace spoke, a few weeks later, at a meeting of the Brixton branch, about militant tactics, receiving a ‘most attentive hearing.’ Grace was tireless and resilient. The WSPU organised events across London during the third week of June 1908. Grace spoke on four consecutive days at outdoor locations; on occasion without support, to a heckling crowd. A few days later, she was in south London doing the same. Grace then joined the demonstration that accompanied another attempt to deliver a petition to the Prime Minister, Asquith, at the House of Commons; this was the suffragettes’ thirteenth attempt. The newspapers report that over three thousand police were drafted into the area. The suffragettes gathered at Caxton Hall, passing through a police cordon to gain entry, before marching towards the Houses of Parliament. Seven women formed the deputation tasked with presenting the petition. One was Dorinda Neligan, the retired founding headmistress of the Croydon High School for Girls, with whom Grace campaigned in Croydon. The group of seven suffragettes set off towards the Houses of Parliament. The deputation was repeatedly refused entry; scuffles broke out in the surrounding area, and the police began arresting women. One was Grace. It was stated she had put her arm around a policeman’s neck in an attempt to free an arrested woman. In a speech, after her release from prison, Grace refuted the testimony. She had seen a woman, wearing suffrage colours, thrown to the ground, and injured by a mounted policeman. Rushing to her aid, Grace put her arm around the woman to assist, not the policeman as claimed. Refusing to be bound over to keep the peace, Grace was sentenced to fourteen days in prison. Although, Grace had heard women speak of their prison experiences; it is clear from an article she wrote for Votes for Women the reality was an eyeopener: ‘We were in ‘Black Maria’ – such a jolting and rumbling I had never experienced before! Was the horror of it all worth the end? Down, down went my heart!’ When the prisoners arrived at prison, they gave a cheer of ‘Votes for Women’ to rally ‘Miss Corson’ who was in solitary confinement. Grace was appalled by the demeanour of the prison matron: ‘Abandon hope all ye who enter here (under her inhuman charge!)’. Grace was placed in a punishment cell for all but one day and night of her sentence, leaving her with no choice but to lie on her bed ‘growing weaker hour by hour’ as she refused food. The prison chaplain tried to persuade her to ‘be a good girl, put on prison clothing, be happy and read nice books!’ Grace found the constant ‘clashing of doors and clanging of keys’ hard to tolerate. Lying awake one night, the moon shone through the window of her cell ‘casting the shadow of a barred square on the wall’, which made her ‘realise more fully than anything else the horrors of the system represented by those cruel bars.’ The third division prisoners cleaned the cells. One was a young woman, around twenty years of age, who Grace asked why she was in prison. The woman whispered back that she had attempted suicide adding ‘This is what it has brought me to. They don’t let you forget it’. Grace writes: ‘Here is work for us to see to after we have gained the needful tool – the Vote’. The encounter made Grace forget ‘the horror of [her]situation … for I saw more clearly than ever the work that lay before us’. Grace was released, along with seven others, having served six days of her fourteen-day sentence. Grace swiftly returned to the campaign, speaking in the pouring rain for over an hour on Streatham Common or travelling to Crouch End in north London to speak; to name two examples of her busy campaigning schedule. The following January, Grace was an integral part of the campaign during the general election in Bradford. Grace, Laura Ainsworth and Mary Phillips addressed up to three meetings each day. Still a driving force within the Croydon branch, Grace realised that selling the newspaper, Votes for Women, on the streets afforded an opportunity to connect with women and explain the importance of the vote. She set out to recruit young women to undertake this work alongside encouraging new speakers: ‘Come, and attempt what you think is impossible! You will succeed. The spirit of suffering womanhood calls you, and we have all had ‘to make a beginning’’. The purpose of obtaining the vote, as Grace saw it, was to give women a voice to tackle evils such as gambling, intemperance or the white slave traffic; ‘it was the burning desire to remedy such evils as these that banded women together in this noble army.’ In the Autumn of 1910, Grace again joined Annie Kenney, campaigning this time in the west of England addressing meetings in Castle Cary, Shepton Mallet and Swindon. On her return, Grace helped to organise a rally in support of the Conciliation Bill at Duppas Hill in Croydon. Three platforms were erected; one of which was chaired by Grace. The WSPU branch, in part thanks to Grace’s efforts, was successfully standing independently financially from the WSPU head office in Clement’s Inn. Grace joined a deputation from nine suffrage groups who marched to the offices of Croydon Town Council to present a petition calling for the vote. The council declined to consider the request as it was a political question. Grace wrote to the local newspaper explaining what had occurred and requesting the paper print her letter ‘for the instruction of the women ratepayers.’ She also wrote another letter addressed to a local councillor, for whom Grace had campaigned, pointing out that he had ‘primed her with [his] political opinions’ and yet, had declined to support the motion to consider the petition as it was a political matter. Her letter closes ‘Trusting you will oblige me with an explanation’. Dorinda Neligan had goods seized for her refusal to pay taxes. A silver teapot, sugar basin and jug, all family heirlooms, came up for auction. Anne Cobden Sanderson, a founding member of the Tax Resistance League, attended the sale along with other supporters. The auctioneer acknowledged that the women wished to protest at the lots being auctioned, giving them the platform. Anne, clutching the League’s banner, addressed the assembled potential bidders, explaining the purpose of the group. The women then withdrew to the street where Grace chaired a meeting. A local journalist confused by the distinction between suffragette and suffragists approached Grace for assistance who explained that ‘gist’ wants a vote whereas ‘gette’ intends to get it. In November 1911, Asquith was the guest of honour at a dinner held at Bedford College for Women. Grace and Leslie Hall succeeded in gaining admittance. Directed to different tables, Grace found herself seated next to Asquith. She introduced herself. Asquith, according to Grace, in evident fear, asked her intention. ‘Wait and see’ she replied. Leslie appeared behind the Prime Minister, and she and Grace explained their position in what was described as ‘a nice little talk’. The two women were then ushered out. One newspaper carried the headline, the following morning, ‘Shameless Suffragettes’. The following year, Grace spoke in Melbourne, Australia, of women’s suffrage calling for more women doctors and chaplains. A Melbourne newspaper carried a report commenting on the ‘graceful way she glossed over the anarchical proceedings of her friends in the homeland’. Throwing a bottle at a car, which potentially held a Cabinet Minister, ‘was lightly touched on as merely symbolic action’, throwing stones ‘was only an act of protest’. The journalist was clearly bemused that the audience was sympathetic. On her return from Australia, Grace continued to campaign and support the WSPU in Croydon. In November 1912, Grace chaired one of fifteen platforms at the Great Demonstration in the East End of London which marched from Bow to Victoria Park. Early the following year, Emmeline Pankhurst visited Croydon. It was widely reported that Emmeline and suffragette supporters had been mobbed. Grace wrote to the local paper correcting the portrayal. A few young men had thrown tomatoes and rotten eggs; ‘such manifestations of bad temper, might, perhaps, by a stretch of imagination, be described as missiles’. The only arrest was of a man who identified himself as a ‘civilian policeman’. Grace closed her letter: ‘When the women get the votes, suffragettes will make a point of throwing a very strong searchlight upon the use and misuse of plain clothes men’. A letter, challenging Grace’s, was published a few weeks later; it asserted the missive was ‘an unpleasant illustration of the type of person who is seeking to achieve notoriety by the suffragette agitation’. By this point, Grace was nearly seven months pregnant with her daughter, Frances, who was born in May. After the birth of her daughter, Grace returned to campaigning. In an attempt to raise awareness of the barbarity of force-feeding, she organised a deputation to visit the clergy of Croydon. One vicar, who had been unaware of the reality of force-feeding, agreed to host a public meeting of the clergy of the town to protest at the treatment. Another was reluctant to be involved but when the women refused to take no for an answer reluctantly agreed to put a resolution before a meeting of the local clergy condemning force-feeding. When Grace gave a speech to the Golders Green branch, she was introduced as the militant who had spent twenty-hours under the platform at St George’s Hall until her moment came to interrupt the speakers. Lydia Grace Williamson was born in 1879 to William, a fish merchant and Celia. At the time of her birth, the family were living in Bermondsey. Grace, as she was known, had three sisters and brother. In January 1900, Grace’s mother died. Ten months later, Grace married Donald Cameron Swan, the son of Joseph, a developer of the first incandescent light bulb. Donald and his father founded the Swan Engraving Company using methods developed by Joseph to reproduce, for example, paintings and photographs. Donald, himself, invented various improvements and was awarded medals by the Royal Society of Arts and Royal Photographic Society. The couple initially lived in Hammersmith but later moved to Sanderstead in Surrey. When Grace was arrested in 1909, she had two small sons born in 1902 and 1903. Donald was supportive of his wife. The Men’s Political Union for Women’s Enfranchisement was founded in 1910; Donald sat on the executive committee holding the office of Parliamentary Secretary. He was also a member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage holding the position of honorary organising secretary. With two others, Donald met with the Member of Parliament for Croydon canvassing for support arguing ‘that the denial of the justice of women’s demand hinders the development of the race, and causes poverty … the complete human point of view is man’s and woman’s combined.’ While Grace chaired one platform at the rally on Duppas Hill in 1910, Donald chaired another explaining the injustice of withholding the vote from tax-paying women. Donald completed the 1911 census return recording he was married, and including his sons, Grace is missing. When Emmeline Pankhurst left for a trip to America during the autumn of 1911, Donald was among the party who gathered at Waterloo Station to bid her farewell. During World War I, Donald served in the Volunteer Battalion of the Queen’s Royal West Surrey Regiment eventually being appointed a Captain in the RAF. Grace was a superintendent, under Lilian Baker, in a high explosive department in Woolwich. She undertook a tour of the munitions factories in France reporting back to Lloyd George, the then minister for munitions. After the war in 1920, Grace was appointed by the Council of the Industrial Welfare Society as the organiser of women and girls’ welfare selecting women supervisors for employers. The newspaper report of Grace’s new role concludes ‘there is no woman in the country who is more fitted to fulfil such momentous duties.’ Grace wrote an article setting out in detail how she viewed her role, the type of women she was seeking to recruit and working conditions: ‘workers have a right to expect healthy and pleasant conditions while performing their duties.’ In 1922, the family emigrated to South Africa to run a guest house near Table Mountain. Grace continued to work to improve industrial conditions and promoting women’s rights. Grace died in 1947 and Donald four years later in 1951. A huge thank you to Iona, Grace and Donald’s granddaughter who kindly contributed and allowed me to use her photographs

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed