|

Hilda Eliza was born, in Quebec, Canada, in 1832, the youngest of seven children of Archibald, an advocate, and Agnes Campbell. In 1854, in Quebec, Hilda married Charles Booth Brackenbury of the Royal Horse Artillery. In August 1857, they had a daughter, Hilda, the first of nine children: three daughters and six sons. During the early years of their marriage, Charles served during the Crimean War and was then posted to Malta. Returning to England, he rose to the rank of Colonel and later acting Major-General. Charles was a respected writer on military topics. Georgina Agnes, often known as Ina, was born in 1865 and Marie Venetia Caroline in 1866. The family was beset by tragedy. In 1870 their eldest daughter died, and in 1884 and 1885 their two eldest sons, William and Charles passed away. Only five years later Charles died suddenly from heart failure. A year later, Hilda’s second eldest surviving son, Lionel, serving in the army, died in India. Hilda left London, and along with Ina, Marie and Hereward, her youngest son. The family moved in with Hilda's sister, Margy, and brother in law, Andrew, an expert in armaments. The couple lived, in a grand style, in Jesmond Dene House, Newcastle upon Tyne. Hilda’s eldest surviving son, Richard, had emigrated to America in 1885 and her other son, Cyril, was abroad working as a mining engineer. Ina and Marie were both artists, who studied at the Slade School of Art. Passenger lists record the two sisters travelling to America, in 1894, where they spent a year. Ina and Marie quickly made the acquaintance of William Keith, an artist in San Francisco, whose friends and pupils they became. The sisters returned to England in 1895. The following year, 1896, the two sisters accompanied by their mother, Hilda, returned to America, remaining until the next spring. William’s brother, Cornelius in his biography Keith, Old Master of California, describes an exhibition held in London, in 1898, by Ina, Marie and their brother, Richard. The latter had bought twenty-four pictures of William’s to London. Although not all of the paintings sold, the press cuttings Richard sent to William, which he in turn sent to the newspapers in San Francisco, led to articles which implied he was an artist of international fame, enhancing his artistic reputation. By 1899, Hilda and her two daughters moved into 2 Campden Hill Square, London. In the same year, William sailed for Europe with John Zeile, an art patron. Marie excitedly wrote to him, offering the use of a studio at their home. For whatever reason, Ina and Marie saw little of William, while he was in Europe, but their correspondence with him continued until he died in 1911. William's second wife, Mary McHenry Keith, was a keen advocate for women’s suffrage. The first female graduate from Hastings College of Law. Mary was a leading member of the Berkeley Political Equality Group, whose activities played a crucial role in securing women’s suffrage in California in 1911. Mary clearly influenced Ina and Marie. In a letter dated 26 November 1908, William wrote ‘Now I will leave a space for Mrs Keith to gossip about woman suffrage.’ In another missive, Marie wrote to William ‘Won’t Mary crow if she gets Woman Suffrage before we do!’ Initially, Hilda, Ina and Marie were members of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, but, in 1908, they joined the Women’s Social and Political Union. Of Hilda, Marie said ‘Night after night we wrestled over the new ideas and her soul was troubled. But she had always been a brave seeker after the truth, and one by one she gave up the old ways of thinking and became fired with the just and true ideals of women.’ The studio, which had been offered to William for his use while in England, became the venue for suffragette meetings. In January 1908, the sisters hosted a suffragette meeting, chaired by Evelyn Sharp, a founder of the WSPU, attended by two hundred women. The following month, Ina and Marie took part in a demonstration outside the Houses of Parliament, which has become known as the Pantechnicon incident. The WSPU hired two Pantechnicons in which to convey forty-two suffragettes into the environs of the House of Commons. Once inside, a petition would be presented. Marie described ‘A great clattering of horses and a sense of jolting and rumbling which lasted for what seemed to use like an age. Suddenly the van stopped, and our hearts beat fast, and the doors swung open, and we saw the House of Commons before us and out we all flew.’ The suffragettes intermingled with the Members of Parliament, entering the House of Commons, but the police grabbed the women pushing them away. Only for the women to try again and again. The suffragette action was part of a three-day Women’s Parliament being held at Caxton Hall. When news reached the delegates of the ruckus, at the House of Commons, many more set off to support the women already there. Ina and Marie were among forty-seven women arrested. Charged with obstruction, they were both imprisoned in Holloway Prison for six weeks. Hilda commented that “I feel that my daughters are doing a service to their country in exactly the same way as my sons would do on the field.” Both sisters, often, spoke at WSPU meetings and rallies. Both chaired platforms at a rally, held in Hyde Park, in the summer of 1908. Of the two Ina was, perhaps, the more active. She lobbied during the by-election in Peckham, south London, and campaigned successfully to prevent Winston Churchill from winning a seat at the Manchester by-election. Alongside campaigning, she was a regular speaker at meetings standing alongside luminaries such as Jessie Kenney; Emmeline Pethick Lawrence or Mary Gawthorpe. Marie was, though, equally highly regarded. She gave an interview to the Northampton Mercury, 22 October 1909. In the introduction, the interviewer describes her as “one of the very best exponents of her cause - a lady of culture and refinement, deeply in earnest.” Maria often used to advertise meetings by using her artistic talents, chalking the details on paving stones or walls. When in 1910, the WSPU felt it needed more women confident to address meetings and rallies, the Brackenbury family lent the studio for weekly classes in public speaking. This was so successful two additional classes were quickly added. Towards the end of 1910, Ina became, along with Rona Robinson, the organiser for Manchester and District. On 12 October, Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst , together with Flora Drummond, were charged with ‘conduct likely to provoke a breach of the peace,’ after they spoke, at a rally in Trafalgar Square, urging people to join them ‘to rush the House of Commons,’ two days later. Christabel, who had a Law Degree from the University of Manchester, but was barred by her gender from practising, mounted a robust defence, even securing Lloyd George and Herbert Gladstone as defence witnesses. The case opened at 10.30 am and continued until 7.30 pm. At that point, the Magistrate asked Christabel how many more witnesses she intended to call. When she announced there were fifty more, the Magistrate adjourned to the following day. However, when the court reconvened, he limited the number to three. After their testimony, the prisoners could address the court. One witness called on the first day was Marie who testified that Horace Smith, the Magistrate who had passed her sentence, had informed her that in sentencing her he was doing what he was told. Hilda took part in Black Friday when she was arrested but released without charge. In March 1912, Hilda, Ina and Marie were arrested for their role in the window-smashing campaign. Hilda, nearly eighty years old, was charged with wilful damage for smashing two windows at the United Service Institution in Whitehall. Ina and Marie were charged with obstruction. The trial of the three took quite some time as all seized the opportunity to address the court at length. All three were sentenced to payment of a fine or two weeks in prison. It is not clear from the records which option the three selected.

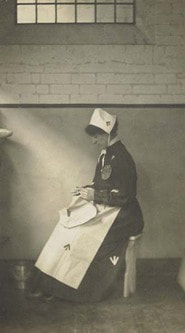

The authorities took to attending suffragette meetings to take notes on the speeches. In one report, the detective boasts he is more than competent at shorthand, his note, therefore, being an almost verbatim transcript. The caveat to his boast is the intended destination of any report and who paid his wages. Even if read bearing this in mind, a transcript of Ina’s speech, given in February 1912, provides an insight into her activism. The meeting was chaired by Christabel, who introduced Ina as ‘one of our best workers.’ Ina opened powerfully: ‘I want you to think for a moment of this Union as a great Regiment; it is a WAR!’ She dismissed thoughts that breaking windows was an act of hooliganism: ‘you are not a hooligan as you are acting in a great and noble cause…’ Ina made a call for one thousand women to damage one thousand windows. This would overwhelm the authorities: ‘1000 women to be tried, 1000 gaping mouths that will want feeding.’ Like a General rallying his men, Ina urged: ‘We must show no weakness, to falter would be to prevent, what we know would be a certain victory.’ When the report was filed in a bundle of evidence for potential prosecution, someone helpfully underscored in blue crayon the words which were considered to be the most significant. Among the files is one which collated all the evidence the authorities had gathered about the WSPU and which was put before two leading barristers of the time, Archibald Bodkin, later Director of Public Prosecutions, and George Branson, later grandfather of Sir Richard Branson. In respect of the Brackenbury women, the documents state that the family home, 2 Campden Hill Square, was let to the WSPU, at £4 per week, who used it as a nursing home at which suffragettes, released under the Cat and Mouse Act, could recover their health following force-feeding. In an article in the Sunday Post, 30 October 1921, Annie Kenney describes being taken by ambulance from Maidstone Prison to the Brackenbury property, which was nickname Mouse Castle. Prior to its use as a nursing home, Campden Hill Square had, temporarily, been used as the headquarters of the WSPU, when their occupation of Clement’s Inn became untenable following a police raid, and the replacement offices at Tothill Street were, in turn, raided. This third move did not, though, deter the police from raiding Campden Hill Square, where, it is noted, they not only recovered WSPU documentation, but also discovered Freida Graham, an alias for Grace Marcon. Grace had been sentenced to six months for damaging five paintings at the National Gallery in May 1914. She was released on 5 June, ill from the effects of a hunger strike and subsequent force-feeding. In a joint opinion, the lawyers, Bodkin and Branson, favoured a civil action rather than a criminal one which they felt was ‘not …likely to succeed.’ In their view: ‘there can be no doubt that the methods adopted and recognised by the WSPU …are unlawful methods, and we think that persons joining or continuing to be members …with knowledge of its unlawful methods, … could be made civilly responsible in damages for injuries maliciously inflicted by other members…’. Both Hilda and Ina were named as persons who could, ‘subject to proof of the facts mentioned’, be joined as defendants. Grace, it was suggested, should be sued in the civil courts by the trustees of the National Gallery for damages incurred. The advent of the First World War put pay to the suggested approach. The family also had a home, Brackenside, in Peaslake, Surrey, which was often used to house women who had been released under the Cat and Mouse Act while they recovered. In an advertisement for a tenant, Ina or Marie described it as a ‘sunny HOUSE, in garden, on hillside above village; beautiful view: four bedrooms, three reception, bathroom, large Swiss balcony.’ Edwin Waterhouse, the founder of the accountancy firm Price Waterhouse and a prominent resident of Peaslake, commented in his memoirs: ‘Peaslake is rather a nest of suffragettes.’ In June 1914, Hilda wrote an impassioned letter to The Times: ‘The women have died, but that did not stop militancy’, continuing, she named women who had died for the cause or those who were ‘partially dead in body though not in spirit.’ Thousands remained prepared to damage ‘pictures, churches, houses …’ but ‘policemen cannot be everywhere.’ Hilda observed that ‘fine young men’ were willing to give up their leisure pursuits to protect property but ‘Let the women die by all means, but to save our young men from such a terrible sacrifice let justice be done, and give women the vote!’ Hilda died in 1918, Marie in 1945 and Ina in 1949. The National Portrait Gallery owns two of Ina’s portraits; one of the 17th Viscount Dillon and one of Emmeline Pankhurst.

2 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed