|

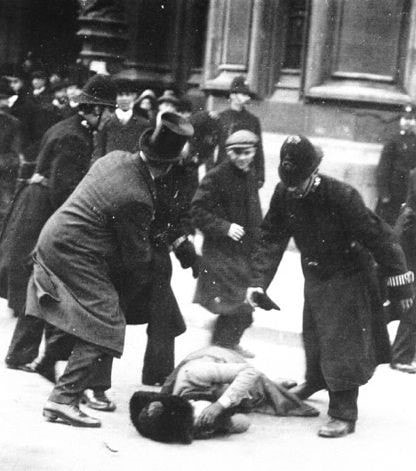

Mary Barnett, born circa 1886, was part of a deputation of women who attempted, in February 1909, to present a petition to the House of Commons. The women marched from Caxton Hall to the Houses of Parliament in single file as ordered by the police. A large cordon of police awaited them outside Parliament which the women repeatedly tried to breach. The newspapers reported that a large crowd gathered to watch, booing or cheering the women’s efforts. Many were arrested, but some returned to Caxton Hall disappointed that they had not been. Four including Mary, then, returned to Parliament from Caxton Hall to have another attempt, but were turned away by the police and when the four stood firm they were arrested. Refusing to be bound over to keep the peace, as she felt that she had done nothing wrong, Mary was sentenced to a month in prison. Mary, whose occupation was given as companion living in Wimbledon, was imprisoned alongside Emmeline Pethick Lawrence. Mary's time in prison shines a light on one of many quandaries the authorities found themselves in when dealing with suffrage campaigners. The official papers include correspondence concerning prisoner’s privileges with Emmeline’s husband, Frederick. One memo sheds light on the authorities’ perspective ‘These ladies avowedly wished to be arrested and have gone to prison voluntarily….it is absurd to allow them special privileges.’ A request to exercise together and converse while so doing was denied. The women, one document states, were disappointed if they did not go to prison and, they could not dictate their terms. The suffragettes had whipped up a furore by encouraging those of ‘a better social standing so that the spectacle of their imprisonment might create the greater effect.’ An issue that had to be addressed, however, was the treatment Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst had been accorded when they were imprisoned the previous year. The suffragettes felt that privileges given to the mother and daughter duo would be granted to all. The authorities felt that ‘the case of the Pankhursts was exceptional and easily distinguished. They were mother and daughter and, the Emmeline's health had necessitated her being many weeks in hospital and so disbarred from associated labour.’ This did not address the issue that Emmeline and Christabel had been permitted to exercise and converse together, a privilege which exceeded the treatment of those in the First Division who were only permitted to communicate with fellow prisoners as a reward for good behaviour. Emmeline was also provided with a daily newspaper ‘on special medical grounds.’ This difference of treatment went on to cause the authorities difficulties for several years.. Nothing else has been found about Mary. Pattie Barrett, aka Martha, was arrested twice in 1907. The February arrest related to an attempt to access the House of Commons. The women marched four abreast, singing “Glory Glory Hallelujah”, headed by Charlotte Despard, as they rounded into Parliament Square the police moved towards them; some on horseback. The women scattered into small groups, all still with the united aim of entering Parliament. Several of the newspapers reported that the police were far from passive in their response. Pattie was fined 10 shillings or a sentence in prison of seven days.Alongside her on the march was her sister Julia Varley who was sentenced to the same. Pattie was born, Martha Varley, to Richard and Martha in 1876. Richard was an engine tenter in a worsted mill which meant he was responsible for the operation of the machine that stretched the cloth as it dried. Julia was five years older than Martha and, the two sisters had seven other siblings, five of whom survived to adulthood. Both Julia and Martha started out their working lives as worsted weavers. Their mother died during the 1890s and, by the 1901 census, Julia is staying at home to care for the family. In June 1899, Martha married George Oliver Barrett, a wine merchant’s bookkeeper, who died only three years later in 1902. According to newspaper reports, following George’s death Julia and Martha moved in together. Whatever the truth of this by the 1911 census return, on which both women are recorded, Martha had returned to live with her father and Julia was living alone having moved to Selly Oak in Birmingham as a trade union organiser. The sisters' grandfather had been a Chartist campaigning for better working conditions and pay. This legacy impacted on most of the family; both of the sisters joined the WSPU. In 1911, two of their brothers worked for the Education Committee Corporation: one as a chef and the other as assistant chef providing nutritious meals for underfed children. While Martha was a registration clerk at the Labour Exchange, having previously worked as a visitor to check on the welfare of poor children. On the sisters release from Holloway, the WSPU in Bradford intended to form a welcoming party at the station. They sent postcards to the women to inform them to get on a particular train, but unfortunately, these were never received. They returned home, on an earlier train, to be greeted by a few friends and family . The WSPU arranged, instead, for a welcome home supper the following week. The two travelled to London towards the end of March to, again, join a protest to the Houses of Parliament. They were two of seventy-six arrested. Martha was fined 10 shillings or a month in prison. Julia stated in court that she wanted to make it clear that she had no complaint against the police, but, she had considerable contempt for the law and the men who made it. She was sentenced identically to her sister. Julia went on to be involved in the trade union movement. Following her retirement, Julia returned to Bradford to live with Martha who died in 1956.  Rachel Barrett © Museum of London Rachel Barrett © Museum of London Rachel Barrett was arrested in 1913. She was appointed editor of the Suffragette and was arrested during a raid on the WSPU headquarters. Sentenced to nine months imprisonment, she went on hunger strike and was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. Rachel’s life is well documented at http://spartacus-educational.com/WbarrettR.htm Janet Barrowman was arrested in March 1912. The daughter of John and Helen she was born in Glasgow in 1880, one of nine children. Her father was a lime merchant who died in 1900. She travelled to London with other Glasgow women to take part in the window breaking campaign. Janet was sentenced to two months in prison with hard labour. At the time, Janet was employed as the chief clerk to David Wilkie, the manager in Scotland of Joseph Watson & Sons Ltd, a leading soap manufacturer, a position Janet had held for over eleven years. She wrote to David from Bow Street police station explaining that she had been arrested and sentenced. He immediately wrote to his solicitors, instructing them to approach the authorities in London. In a lengthy letter, David provides the background. Janet had requested a couple of days of holiday to travel to London. As a business, they had been swamped and Janet ‘had done her full share.’ David felt the break would do Janet, who was in his view, ‘very sensitive and highly strung’, good. David did not have the exact details of what had taken place. He was aware that Janet was interested in the votes for women campaign and suspected, that in connection with the campaign, she had ‘exercised her abilities and resources …somewhat to the same extent as she does in connection with my business.’ This, he felt, had brought Janet to the attention of the WSPU leaders who frequently visited Glasgow. In his opinion, Janet would have hesitated, before behaving as she had done in London, if she was in her home town, he observed, commenting ‘she has been too well looked after by people who ought to have known better.’ Within his work, David demanded that his employees kept ‘well the limits of the Law and decency’ which he felt Janet would have done ‘if left to herself.’ Janet was entitled to fourteen days annual leave which would be used in full before her sentence was served. Once her holiday entitlement had been used, David would have to notify the head office who would, he believed, order him to dismiss her. Janet was an integral part of the business who took control in his absence. Not only would the consequences by cataclysmic for Janet’s future, but they would also impact on her family, in particular her widowed mother who was ‘prostrated with shock.’ Janet’s health, David wrote, required ‘serious care’ as ‘her heart is affected, and she is anaemic’. He clearly regretted not questioning Janet more closely as to her reasons for travelling to London. David’s solicitors, Wright, Johnston & Orr, wrote to Reginald McKenna, the Home Secretary, making representations and enclosing his letter. The view of the authorities is evident from an internal memo: ‘loss or damage to businesses may have some deterrent effect’ which remark entirely misses the thrust of David’s letter. The memo continues that it would be unwise to meddle with the sentence as ‘it seems so essential … to impress on the violent suffragettes that they will be held to undergo the full consequences of their acts of lawlessness.’ Another memo notes that sentences could not be apportioned according to the value of the window, but a ‘broad distinction’ was drawn between over and under £5. This, in no way, addresses the reason why suffragette sentencing differed widely. A fact not lost on David who then turned his attention to the disparity in sentencing, which is also very clear from this research thus far. Mrs Brackenbury and her two daughters, the widow and offspring of a General, were sentenced to fourteen days. The window Janet broke was valued at 4 shillings, and by David’s calculations, the Brackenbury’s must have broken windows valued at 1 shilling for the sentences to be comparable. While David felt these matters should be dealt with seriously, sentences should be given ‘without respect of persons’, in other words class. Others joined in questioning the severity of the sentences, of not only Janet but, others from Glasgow, again highlighting the Brakenburys. Janet is credited with helping to smuggle out poetry from Holloway which was published by the Glasgow WSPU as Holloway Jingles. She, as David predicted, lost her job but successfully found an alternative. Elsie Bartlett, recorded as born in 1889, was charged with window breaking on 1 March 1912 and was sentenced to one month’s imprisonment. Her crime was to break a window at No 4 Grand Hotel Buildings with a hammer causing damage said to amount to £4 10s. In court, Elsie said: “I wish to say that I am very sorry that my protest had to take this particular form, but it is the only argument to which this government will listen.” Alice Barton was arrested in November 1910 for breaking a window and was sentenced to two months imprisonment. Mary Bartrum, whose full name was Mrs Doris Mary Bartrum, was part of a deputation to the House of Commons with the aim of seeing the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith. The protest had been organised because Asquith had reneged on the Conciliation Bill, which would have given property-owning women, over thirty, the vote. The bill passed its second reading, but Asquith declared there was no Parliamentary time for a third reading as Parliament was to be dissolved. The suffragettes were incensed. The deputation was corralled by the police and forced to stay in one place where all they could do was watch the events unfurl. For four and half hours, hundreds of suffragettes struggled with the police who were on foot and on horseback. The police’s approach was to wear the women down rather than arrest them. The women were met with beatings, batoning and punches. The Daily Mirror published, a few days afterwards, a picture of suffragette Ada Wright on the ground. As one eye witness reported, she was bodily lifted and thrown back into the crowd. When she reapproached, a policeman struck her with all his force knocking her to the ground, as she tried to get to her feet, she was struck again. As the picture shows a man remonstrates with the police, but he was swiftly moved on. After knocking her down, again and again, she was left lying by a wall of the House of Lords. As more women marched towards the House of Parliament, their banners were snatched from them by the police, while they kicked or punched the women. Some women claimed they were sexually assaulted. Only after four and half hours, did the police take to arresting the women rather than trying to wear them down. One hundred and nineteen were taking to the cells. In reports, included in Votes for Women, the women placed the blame at the drafting in of policemen from other areas who were not well trained or used to dealing with women. ,When Winston Churchill became aware of the photograph that the Daily Mirror had taken, he tried to suppress it, but they refused, publishing it on their front page. Its publication led to calls for an enquiry into the day’s events which Churchill refused. The day became known as Black Friday.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given the outcry at the women’s treatment, the Home Office decided to offer no evidence at court and the women were discharged. Many questioned the reasoning behind this and felt the decision had been made as an election was coming up, and it was an attempt to mollify the women. The suffragettes saw it as a victory due to the generally supportive press coverage and the clear acknowledgement, in their eyes, that the government felt that any stand against them would make them unpopular at the forthcoming election. Doris was born in October 1882 in Kensington, London to George, a produce merchant, and Janet. The family settled in Eastbourne, East Sussex. By 1901, George had retired, and the family had moved back to London, settling in Hampstead. The family were comfortably off, at sixteen, Doris was still at school, and they had a live-in housekeeper. One of three children, Doris married John Edward Bartrum on March 24th 1906. John was a mantle manufacturer for gas lamps, and a seller. The couple had two daughters, Joanna born in 1908 and Bridget in 1914. John completed the 1911 census return where Doris is recorded as working as a commercial traveller in his business. Other than her name, her occupation, numbers of years married and number of children. No other details are recorded about Doris such as date or place of birth. This is true of the other women in the house on census night: Alice Glover single, Kate servant. Only her daughter’s and husband’s details are recorded in full. Someone, presumably Doris, has written in large red writing “VOTELESS Women of Household only prevented by illness from evading census, therefore have refused to give information to occupier”. John and Doris divorced in 1918. The following year Doris married John Mackie. Doris died on December 27th, 1933.

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed