|

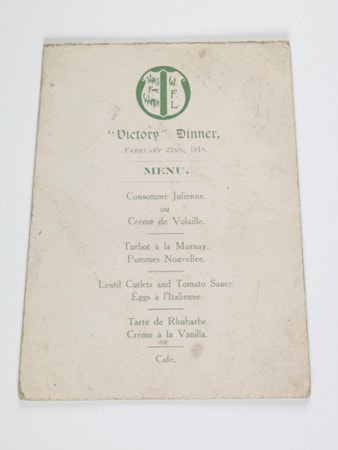

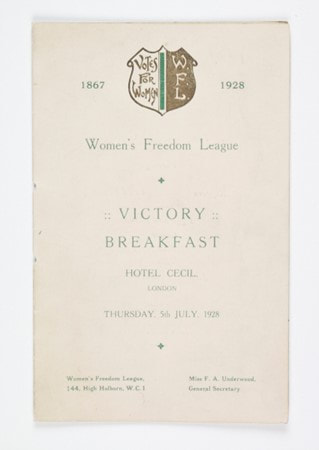

Myra Eleanor Sadd-Brown was arrested twice: November 1911 and March the following year. In 1911, Myra was one of around two hundred suffragettes arrested. Charged with obstruction, she was sentenced to a 5-shilling fine or five days in prison. She elected to go to prison. Myra Eleanor Sadd was born, in 1872 in Maldon, Essex, to John, a timber merchant, and Mary Anne. The second youngest of ten children, five girls and five boys, Myra grew up in Maldon, where her family were members of the Congregational Church. Besides his business interests, her father was Mayor four times of Maldon, a visiting justice to the Essex County Lunatic Asylum and a Harbour Commissioner. A Liberal, John instilled in his children the importance of hard work and service to the community. Myra married Ernest Brown, a hardware merchant in September 1896. She followed other liberal-minded couples and, from her marriage, was known as Sadd Brown. The couple lived at 34 Woodberry Down, just off Green Lanes at the northern tip of Finsbury Park. They had four children: Myra Sadd, 1899; Ernest Sadd, 1904; Emily Price, 1906 and Jean Frances, 1908. Ernest and his brothers established Brown Brothers Limited, based in Great Eastern Street, Shoreditch, with branches across the country and representatives in Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa and South America. The business retailed bicycles, motorbikes and, at one point, cars plus any parts required. Ernest was a member of the Worshipful Company of Tin Plate Workers. An entity whose application form presumed only a male applicant. All four children followed in their father's footsteps. On the girls' forms, son is crossed out. Myra was elected a poor law guardian serving on the Hackney Board for six years. On Edward VII's coronation, Myra donated sufficient strawberries and sugar to feed around eight hundred elderly and infirm residents in the Hackney Workhouse. A donation she repeated in following years, providing over four hundred pounds of fruit each time. A member of the Women's Liberal Federation, Myra attended a conference in Birmingham in May 1901. One woman called the assembled company' political dummies' if they supported any candidate who disagreed with women's suffrage. Another pointed out that without the vote, women were classed 'with paupers, lunatics, criminals and children,' Despite these pleas, the motion to only support candidates who were pro-suffrage was defeated. Another significant issue was the Boer War with the proposed resolution that the encounter was 'all wrong from beginning to end.' With several others, Myra countered the proposal with 'considerable vigour,' observing why 'our Army and ourselves' were being painted 'as black as possible and the other side as white and as pure as the driven snow?' This statement was met with widespread approval. In January 1903, Myra addressed a meeting of the Romford Women's Liberal Association. In a speech entitled, The Ideals of Liberalism, Myra stressed the importance of women taking their place in politics. Women needed to be organised in their campaigning 'without which they were like a rudderless ship' undertaking 'to do their share of the fighting for the freedom and privileges of Liberalism which … would again be the might movement it had been in its best day.' Myra's mother, Mary Ann, was President of the Maldon branch of the Association. At the family home, Mary Ann hosted a gathering at which Myra spoke about women's suffrage. At the annual conference in Halifax, Myra moved a resolution condemning the proposed London Education Bill, which, if passed, would see women unable to stand for election to education authorities, an arena in which they had previously made significant contributions. The resolution easily passed. At the evening reception Earl Beauchamp, a Liberal peer, added his support, voicing his opinion that the Bill was 'a failure.' In April 1904, Myra ceased to be a guardian. At her final meeting, it was observed that Myra 'had the mind and courage of a lady combined with the inferior power of a man.'  ©Museum of London Commercial picture postcard published by the Rotary Photographic Company. The comic postcard is printed with two studio photographs of a young female child representing the Suffragette both 'at home' - reading a newspaper and 'at work' - standing on a chair delivering a speech. The postmark is dated 15 August 1909 and includes a message possibly sent to the Suffragette Myra Sadd Brown. It notes the sender is going to the White City Exhibition the following day. By July 1907, Myra was secretary of the North Hackney Women's Liberal Association, part of the Federation, which she set about re-organising. In the same year, she donated £5 to the WSPU's £20000 fund. At a meeting of the Federation at Caxton Hall, it was proposed, as it had been in Birmingham, that support should only be extended to candidates who supported women's suffrage. Myra sought to extend the proposition to refusing to assist in any electoral activity unless 'a measure for [women's] enfranchisement' was brought in. It appears that Myra's proposal was not accepted and she left the group. The Women's Franchise, the WFL newspaper, announced in October 1908 that Myra was to be one of the speakers at Caxton Hall. Despite this allegiance, she and Ernest donated £5 each to the WSPU £50000 fund. Myra joined the Hackney branch of the WFL chairing in December 1908, a two-day gathering in the Stoke Newington Library Gallery. Speeches by Charlotte Despard, Teresa Billington-Greig, were followed by performances from the South Palace Orchestra and the gallery was filled with stalls offering needlework, dolls or pictures for sale. From 1909 onwards, Myra addressed WFL meetings regularly. At an At Home held at Caxton Hall, Myra explained why she had abandoned the Women's Liberal Federation which, had become 'hide-bound' by putting 'the cloak of party right round them.' Myra spoke at a meeting of the New Constitutional Society for Women's Suffrage, an organisation formed, in 1910 after the General Election, to lobby the Liberal Members of Parliament on the subject of women's suffrage. The family had by now moved to 2 Chesterford Gardens, a substantial red brick house, in Hampstead; while they often spent the summer months in Essex. At some point, the family purchased Crossways in Little Baddow, where Myra would host events. Ernest's business interests were flourishing, and Myra was supported in her domestic role by three maids and a children's nurse. In March 1912, Myra was charged with breaking a window at the War Office. At her trial, Myra's lawyer, who also represented Catherine Richmond, pleaded that they 'got carried along by some people behind them.' The magistrate was unimpressed, observing, he 'could understand a young girl being carried along, but these were middle-aged women,' before sentencing them to two months with hard labour. The WSPU newspaper, Votes for Women, kept its readers appraised of how the prisoners were fairing. Myra went on a hunger strike. One prisoner, on her release, reported that attempts had been made to forcibly feed Myra by nasal tube, despite being made aware that she had previously broken her nose and had her throat operated on. The forcible feeding resulted in bleeding from her nose and throat. Following her release, Myra wrote to the Daily Herald detailing her experiences. She had decided to refuse food in protest that the privileges which could be accorded to prisoners should not be 'withheld according to the discretion of one man.' When it was decided to commence feeding by the nasal tube, no examination of Myra's nose was made despite the doctor being aware of her medical history. It took four attempts to pass the tube through one of her nostrils successfully. Myra informed the Governor of her previous medical history but, despite her plea, force-feeding was attempted again the following day. After four attempts, the procedure was abandoned. Myra wrote, 'I do not wish to speak of my mental or physical sufferings; they are indescribable.' Keir Hardie asked questions in the House of Commons concerning Myra's treatment to which Ellis Ellis-Griffith, Under-Secretary of State for the Home Office, responded that if she 'suffered any pain it was due entirely to the violent resistance she offered in the form of 'the unusual power she possessed of contracting the throat muscles, and expelling the tube.' Ernest wrote to the Prison Governor, forwarding a copy to the Home Secretary, (see below for a link where you can listen to the letters Myra and Ernest exchanged) the day after Myra's release on 29 April. He had learned of the force-feeding from the Press but had decided to refrain from writing until he had heard Myra's account. Ernest recounts the facts, commenting that Myra's treatment had given her 'a severe shock.' He questions why, despite Myra informing the medical staff of her history, no examination was conducted.In his covering letter to the Home Secretary, Ernest demanded an enquiry. The doctor concerned wrote a report to the Prison Governor confirming that he had been made aware of Myra's medical history and had reassured her 'that if an obstruction did exist the soft rubber tube was the safest and most gentle instrument for ascertaining its presence.' No such obstruction was found; the issues were caused by Myra's ability to expel the tube. He had not observed any bleeding nor, he contended, had Myra informed him of any such occurrence. A different doctor had attempted the procedure the following day. The same issues occurred with the nasal tube, and therefore he decided to use the oesophageal one instead. Before this was attempted, the prisoners decided to take their food and, Myra joined them. In concluding, the doctor described Myra as 'violently resistive.' Myra was also a supporter of the Women's Tax Resistance League. In January 1913, she hosted an At Home at which Louisa Garrett Anderson spoke. Myra also supported the Church League for Women's Suffrage, whose founding aim was to secure the vote in Church and State as it was granted to men. At their Spring Fair, held at a Congregational Church Hall, Myra ran the refreshment stall. At the same time, Ernest donated £10 to their funds. In June 1913, Myra was elected to the executive of the Church League for Women's Suffrage. By 1914, Myra appears to have aligned herself with the East London Federation of Suffragettes while continuing her work with the Church League for Women's Suffrage. Formerly the East London Federation, it was founded by Amy Bull and Sylvia Pankhurst, in 1913, on democratic lines and allowed men to be members. Early in 1914, the group was expelled from the WSPU and altered its name. At the same time, the Federation launched the Women's Dreadnought newspaper. In an attempt to raise much-needed funds members, were encouraged to participate in a self-denial week. Myra and her family lived off nothing other than bread and cheese for a week donating the funds saved. Myra purchased copies of the Women's Dreadnought for distribution. By the end of 1914, Myra was involved again with the WFL, supporting the Women's Suffrage National Aid Corp, founded to provide women and children with assistance who were financially suffering because of World War I. Much of this work centred around Charlotte Despard's premises in Currie Street where children could stay, if their mothers were hospitalised, nutritious vegetarian meals were provided, or women remunerated for sewing clothes in a workshop. Myra hosted an At Home where Charlotte spoke of the support working-class women and children needed. Similarly, Myra hosted an At Home to raise funds for the East London Federation of Suffragettes. The Federation organised, at Caxton Hall, a two-day exhibition where various suffrage societies had stall. Alongside, a Women's Labour Exhibit which included a sweated labour section, demonstrating the work of brush, matchbox and garment makers; an area displaying the products of the East London Toy Factory and a demonstration of the reality of price increases. Myra ran the refreshment stall. In June 1915, the Hampstead Branch of the WFL hosted a gathering to celebrate Charlotte Despard's birthday. Myra's children performed a selection of French plays, described as 'charming.' Both Ernest and Myra generously financially supported the Federation both on a monthly and ad hoc basis. At a Church League prayer meeting and tea table conference, the discussion centred around whether women should serve on War Tribunals established to decide whether or not a man should be sent to the Front. Several women felt strongly that as a man could not decide to send a woman into battle, it was wrong for a female to decide as the woman's movement stood for equality. Myra succinctly argued that the sex of the Tribunal was indifferent 'provided the spirit animating the deliberations was the same.'  ©Museum of London Printed menu for a 'Victory" Dinner' held by the Women's Freedom League on 22 February 1918 to commemorate the passing of the Representation of the People's Act that gave certain women over 30 the right to vote in parliamentary elections. Headed with the logo of the Women's Freedom League the dinner, in keeping with others organised by the WFL, comprised a vegetarian menu in this case with a main course of Lentil cutlets and tomato sauce. The menu has been signed by many of those attending the event including Myra Sadd Brown and Maud Fisher. Myra was a pacifist and, after the end of World War, I represented the Church League at a Peace Conference held in Manchester. In 1916, the League changed the name of its newspaper to The Coming Day, the new title suggesting 'that we lift our eyes from the black and turgid present to a future of a clear-shining morn.' By 1920, the aim of the newspaper was to provide a platform with 'high aims such as the League of World Friendship.' Myra was appointed the treasurer. Her financial support of the Federation and the WFL continued alongside her fundraising work for the Russian Relief Fund and her support for a Royal Commission's call to investigate cruelty in asylums. Myra often chaired discussions organised by the WFL Hampstead Branch. Myra's eldest daughter, also named Myra, joined the WFL, representing those under thirty years of age. She gave a talk on the right of university women to share in political affairs; men had the vote at twenty-one, women at thirty. Mother and daughter were part of a deputation that presented the argument for equality of political rights at the House of Commons. Emily, Myra's second daughter, assisted at the gatherings of the Hampstead Branch. The British Commonwealth League was founded during the 1920s to 'promote equality of liberties, status, and opportunities between men and women and encourage mutual understanding throughout the Commonwealth.' Many of its members were campaigners for women's suffrage. Myra was the League's first treasurer and sat on the Women's Advisory Council of the League of Nations Union as a representative of the British Commonwealth League. In 1928, to raise funds and awareness, she organised an excursion to Crossways, the family home in Essex. In 1919, the League of Nations was founded. Many women's groups sought to ensure that women had a role to play and, a year later, in 1920, the Council for the Representation of Women in the League of Nations was established with the aim of ensuring women formed part of any British delegation to the League. One of the groups affiliated to the Council was the WFL. The executive of the WFL nominated Myra to be a vice president.  ©Museum of London A souvenir menu and programme issued for the Women's Freedom League Victory Breakfast held at the Hotel Cecil on Thursday 5 July 1928, to celebrate the passing of the Equal Franchise Act. On the reverse are signatures of many suffragette prisoners who attended the event including Teresa Bilington Greig, Edith How Martyn, Myra Sadd Brown and Mary Richardson. Included in the breakfast menu were porridge, kippers, fried plaice, eggs and bacon, omelette, boiled eggs, jam marmalade and toast. On 12 July 1930, Ernest died. The Vote described Ernest as 'a generous friend of the Women's Freedom League (Nine Elms Settlement), and was particularly kind and sympathetic.' Myra continued with her work. Presiding over a WFL event in 1932, she said the League 'pursued a line of continuity and never forsook its ideals…[It] worked with a resolute persistence.' Words that could have been written about Myra herself. In 1933, Myra stood successfully for election to the National Executive Committee of the WFL. In that capacity, she was one of the delegates to the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship held in Istanbul in 1935.

In 1937, while abroad, Myra died. The International Women Suffrage News spoke of Myra's 'constant service to the women's movement' and her 'certain tranquil faith in the rightness of that cause which was an encouragement and inspiration.' At suffragette dinner in 1939, Myra's daughter, Myra, recollected, as a thirteen-year-old girl, handing out pamphlets on the Commercial Road and visiting her mother in Holloway Prison. 'They did a great thing these women. I am grateful to them.' Two years ago, Myra's granddaughter, Diana, collaborated on a podcast called Your Loving Myra, in which some of the letters between Myra and Ernest, written during her time in Holloway in 1912, are read. It is well worth a listen https://soundcloud.com/bethmoss/your-loving-myra. Their love and his support for Myra shines out. The LSE library also holds poignant letters from Myra's children to her while she was in prison.

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed