|

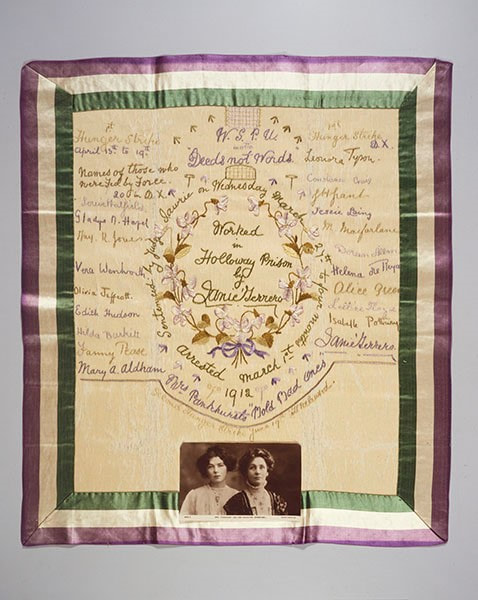

Hilda Evelyn Burkett, or Byron, an alias she sometimes used, was arrested, according to the amnesty record four times. Born in 1876, her given name was Evaline Hilda. At the time of her birth, her family lived in a substantial house, Wilton Lodge in Tettenhall, a prosperous area of Wolverhampton. Hilda’s father, Reuben, was a hardware merchant but also collaborated extensively with Edwin Godwin, an architect and designer, on the provision of furniture for Dromore Castle. The Irish Builder, 1 March 1869, includes an extensive advertisement for the services of Reuben Burkitt & Co, a company operating as builders’ ironmongers and machinists. Alongside his business activities, Reuben was a poor law guardian and a member of the Wolverhampton town council. In 1883, his business which had been turning over more than £20000 per year, ran into financial difficulties. Unable to pay its debts, an arrangement was entered into with the creditors. One newspaper carried the headline ‘Failure of a Wolverhampton Town Councillor’. At the next council meeting, Reuben resigned. Not one word of thanks for his service was reported and, when a candidate for election came forward, the newspaper reports noted that the vacancy had occurred due to Reuben's bankruptcy. The 1881 census return records Hilda residing with her paternal grandparents, Charles, a retired builder, and Clarissa, in the village of Keresley, Coventry. By 1891, her family had moved to 133 Lodge Road, Winson Green, Birmingham, while Hilda remained living her with her, now, widowed grandfather. Reuben had become a commercial traveller specialising in hardware. He is absent from the family home when the 1891 census was taken. Hilda’s mother, Laura, is noted as the head of the family, while Reuben is recorded staying at lodgings in Portsmouth. Ten years later, Reuben and Laura had moved again to Handsworth in Birmingham, while Hilda had moved in with her second elder sister, Laura Christobel, and her husband, and was living in Aston, Birmingham. Her younger sister, Adelaide, had passed away four years previously and her eldest sister, Ida, had moved to London to work as an actress and authoress. All three of the surviving sisters would play a part in the fight for women’s suffrage. By December 1907, both Hilda and Ida were supporting the WSPU; each donating a shilling to the £20,000 appeal for funds. A little over a year later, Hilda was charged with obstructing the police during a political meeting in Wolverhampton. In court, Hilda said she was there to protest against the Government. The Chair of the Magistrates responded with ‘Oh, botheration! Go back to Birmingham, and don’t bother us again; you ought to be ashamed of yourself’. Hilda, now living in Sparkbrook, Birmingham, was member of the WSPU Small Heath and Sparkbrook Branch. Early in August 1909, Hilda was arrested along with eight others in Hull and charged with disorderly conduct. During the previous evening, the women had gathered outside the Assembly Rooms, where Herbert Samuel, a Liberal Cabinet Minister, was due to make an address on the implications of the Budget. One policeman described the women as being ‘in a very excitable condition’, waving their arms and shouting ‘Votes for Women’. This behaviour the police witnesses asserted caused ‘a large crowd … to assemble’. When the nine refused to disperse the police arrested them. In court, one of the policemen struggled to give any evidence other than the women had drawn a crowd, an assertion which caused hilarity among the supporters in the gallery. Charlotte Marsh, one of those arrested, testified that the purpose of the women’s attendance was to protest at the inability of women to vote while they were expected to pay taxes. The planned gathering had been announced by chalk advertisements on the pavements. All the arrangements had been made by her, as the Yorkshire organiser of the WSPU, and the part the other eight defendants played was minimal. Several of the nine, including Hilda, asserted that they had not shouted out until the mounted police had ridden onto the pavements to disperse them. When concluding the proceedings, accompanied by hisses from the gallery, the Magistrate stated, ‘I am not going to gratify any wish which any of you might have to make martyrs of yourselves by undergoing imprisonment’ and discharged all nine. Hilda returned to Birmingham holding numerous meetings across the city, often, supported by Laura Ainsworth. When the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, visited Birmingham during the Autumn, Ellen Barnwell and Hilda threw stones at his departing train. The pair were jailed for one month in Division II, in Winson Green gaol. This event has been commemorated at Birmingham New Street station with a mural. Among Hilda’s fellow prisoners were Laura Ainsworth and Charlotte Marsh. All three, alongside others, refused, on admission, to wear prison clothes or take any food. Having been without sustenance for over two days, Hilda was taken before the Prison Governor accused of breaking three panes of glass in her cell. As Hilda was weak from lack of food, no punishment was given. While in the Governor’s office, Hilda wrote a petition requesting removal to Division I. In the evening, Hilda was taken to the prison hospital and given a pint of hot milk, which she refused to drink. Tuesday, day three of her interment, Hilda again declined milk. Later, she was taken to the hospital kitchen where two doctors, four wardresses and matron were assembled. Placed in a chair, covered by a blanket, it rapidly became clear to Hilda that an attempt was to be made to force feed her. She shouted out ‘I will not take food! I refuse! I will not swallow!’ Her lips were prised open, and milk poured in through the crevices of her teeth. Hilda did not swallow and after thirty minutes the attempt was abandoned. The doctor then made two attempts to insert a nasal tube but by coughing Hilda expelled it each time. She was then returned to her cell. Hilda informed the wardresses ‘This, I think, will kill me sooner than starving; I can’t stand much more of it, but I am proud you have not beaten me yet’. Less than two hours later, and with a now very sore throat, Hilda was returned to the hospital kitchen. The cup was attempted repeatedly. Each time, Hilda refused to swallow. An attempt was made to use a tube. Broken not beaten, Hilda agreed to the cup. This was repeated every two hours. Hilda realised that the other women from the courts, had joined her when she heard, through the walls, a line from La Marseillaise ‘Are we of meaner soul than they’. Hilda took food, until the following Monday, to ensure she was returned to her cell near the other women so she could tell them what had happened to her. On the Monday, she took breakfast but then refused food until Wednesday evening when she was forced into a reclining position, her head tilted back, and liquid poured in. The treatment was taking its toll on Hilda who was placed in the prison hospital until her release. The treatment of the women prisoners gave rise to a considerable amount of publicity and correspondence. The Home Office files include differing medical opinions as to the impact of force feeding, interspersed with reports on the condition of the prisoners: 3 October 1909 ‘Hilda Evelyn Burkitt is not very well this morning owing to a restless night. She is taking nourishment well and without opposition’ 4 October 1909 ‘Hilda Evelyn Burkitt takes food of her own accord and is gaining strength again’ 7 October 1909 ‘Hilda Burkitt is about the same she takes food willingly’ One, dated 13 October, notes that Hilda had been given an enema to relieve constipation and was ‘taking nourishment fairly well’. It appears that Hilda, by this point, was not being force fed as details of the method used is given for each prisoner and in, her case, there is no mention of either a nasal or oesophageal tube. Two days later, the day before Hilda and Ellen were due for release, a report notes that both had been examined by two doctors who concluded that they were both in good health and ‘free from injury’. Ellen was still being force fed while Hilda was not. Despite the assertion as to their health, The Times, 18 October 1909, describes Hilda having a bruised face from force feeding. As it is clear from the reports that it was sometime since Hilda had been force fed the presence of bruising on her release indicates the amount of force which had been used earlier. Following her release, Hilda returned to her home in Sparkbrook, giving an exclusive interview to a Daily News journalist, who described his interviewee as speaking ‘feebly in an undertone’ while ‘stretched on a couch’. Her father had summoned a doctor who reported that Hilda’s heart was weak in consequence of force feeding. Hilda explained that while in prison she had gone on hunger strike three times ‘once for 81 hours, another time for 76 hours, and on the last occasion for 24 hours’. She continued that, initially, an attempt had been made to use a feeding cup but when she refused to swallow the oesophageal tube was used. When the feeding cup was next presented, she drank from it. The women had kept their spirits up by greeting each other in the mornings with ‘Are we downhearted? No surrender!’ As the interview ended, Hilda said that violence was ‘still justified … as the only method of agitation open to the Suffragists’. By November, Hilda was back campaigning. Eva Dixon and Hilda travelled to Walsall to hold an open-air meeting. As Hilda spoke, she was heckled, pelted with rotten apples, and pushed off the chair she was standing on. The two women were forced to retreat. During the evening, Eva and Hilda attempted to speak again but the response was equally negative and again, they were forced to abandon their efforts. Throughout the following two years, Hilda was a regular speaker at meetings often talking of her experiences of force feeding and current militant strategies. In April 1912, Hilda was arrested and charged with malicious damage to four windows, at 102-103 Bond Street, valued at £40. An additional charge of breaking a window at 105 Bond Street was dropped. In court, Hilda stated that any damage was not malicious and ‘it was time this fight was put a stop to, they did not want to spend their lives in prison, but they did want to remove the stain and stigma on women’. Refusing to be bound over, as Hilda considered it ‘a disgrace to womanhood to do so’, she was sent to Holloway Prison for four months. A note on the files reads ‘convulsive hysteria …mentally unstable’. Hilda petitioned, as a political prisoner, for ‘her own work my books, my writing materials and receive and send letters once in two weeks and also I wish to have fruit sent in by my friends, and various parcels of clothing and so on. I also require my watch and brooch, and I insist on having two exercises a day for the sake of my health’. On her petition, Hilda’s behaviour is noted as ‘bad’. Her requests were denied. Again, Hilda was force fed, although the files do not contain any specific details. She was released, on 26 June, having been in the prison hospital under observation for six weeks. A report written on the day of her release states she is ‘mentally very unstable … owing to the doubtful hysterical condition’. Therefore, immediate release was recommended. By January 1913, Hilda was living in Stoke on Trent, the organiser of the newly founded Potteries Branch of the WSPU. At one of the first meetings, Hilda spoke about militant action: ‘They had found that peaceful methods were of no avail, and the opposition of the Government had compelled them to resort to more drastic measures’. If the Adult Suffrage Bill were not passed the truce would be over and the inevitable conclusion was, Hilda stated, ‘that they had not been militant enough’. Any action not injurious to human life would be pursued. In April, George V visited the Potteries. Hilda wrote to the Daily Herald complaining that ‘all they saw was a dim outline … inside a dark motor car’. This was because ‘it was openly admitted that the Royal personages had the fear of the Suffragists in their hearts, so they dare not ride in an open carriage, or even have the windows of the motor car down’. This Hilda felt indicated ‘that at least the powers that be, are beginning to feel our power’. Hilda was true to her word where militancy was concerned. She was arrested on 27 November 1913, alongside Clara Giveen, charged with setting fire to a football stand in Leeds. Both were remanded in prison to await trail. For some time, after her arrest Hilda was known as ‘prisoner B’ as she refused to reveal her identity. An attempt was made to take her fingerprints by the wardresses but, when this failed, the Prison Governor drafted in male staff to assist. Hilda resisted throughout and broke several cell windows in protest. Hilda refused food from her admission but was not force fed. A report, dated 1 December, suggests force feeding should be considered, but, two days later, her condition had deteriorated, to such an extent it was not thought safe to proceed. Therefore, Hilda was released under the Cat and Mouse Act into the care of Mrs Whitehead of Bradford, on 3 December, to return six days later. The medical report, on the day of her release, notes that ‘prisoner is much weaker today – remains in bed all day’. Mentally, Hilda was ‘emotional’, unable to sleep; physically she had ‘cold extremities’ and a ‘rapid and thin’ pulse. A telegram was sent, to the Chief Constable of the Leeds Police, by the Home Office notifying him of Hilda’s release and ordering that ‘careful observation should be kept on her movements’. Neither Hilda or Clara, also out on licence, appeared in court and the trial was adjourned until April. By which time, Hilda was in Suffolk. On 28 April, she was arrested, alongside Florence Tunks, and charged with setting fire to the Bath Hotel in Felixstowe, causing damage of, it was estimated, £30000, two wheat stacks at Bucklesham and another stack at Trimley. Hilda gave her name as Byron. Both appeared before the court in Felixstowe the following day and were remanded in custody for a week when they were brought before the court and, again, placed on remand. ,A report, among the Home Office files, states that the police set about finding two women who had, on the night of the hotel fire, been absent from their lodgings. Hilda and Florence had been staying at Mayflower Cottage. On the evening in question, the two had told their landlady they were travelling to Ipswich and would return the following day. However, evidence indicated that Hilda and Florence had, in fact, been at a beach tent close by to the hotel. The police attended Mayflower Cottage, searching their rooms, where they found ‘a hammer, a glazier’s diamond, a pair of pincers, and a bottle containing phosphorous in water’. It was believed that entry had been gained to the hotel by cutting out part of a pane of glass which had ‘been smeared with soft soap and covered with wadding’. A tin of soft soap was found at the beach tent. Nearby, labels, such as those found at their lodgings, were discovered with phrases on such as ‘There can be no peace until women get the vote’ or No votes means war, votes for women means peace’. The final piece of evidence was a letter to Hilda, sent the afternoon after the fire, in which the writer opened with ‘Just heard about your latest and congratulate you’.

While Hilda was on remand, the Suffolk police linked the arson attack in Felixstowe with a fire at the Britannia Pier in Great Yarmouth: ‘It is significant that these women were in lodgings at Great Yarmouth at the time of the fire … and on that night similarly were absent from their lodgings all night’. This deduction was supported, it was argued, by a letter found amongst Florence’s possessions in which a friend mentioned doing building work in Norfolk. The report concluded by requesting the involvement of the Director of Public Prosecution ‘as the actual evidence against these women will be exceedingly difficult to place properly before the Court’. What becomes clear, from the files, is that the Home Office were convinced that Hilda had been responsible for other arson attacks. When her lodgings were searched Hilda’s 1914 diary was taken. Entries were compared with reports in the Suffragette and other newspapers of ‘outrages committed by members of the Women’s Social and Political Union’. These, in italics, are two entries: Diary: Jan 25 to Dunkeld AM On 24 January, an explosion occurred at the Botanic Gardens in Glasgow and Bonnington House in Lanark was found on fire. Helen Crawfurd, a Scottish suffragette, was, later, found guilty of the fire at the Botanic Gardens. Charges were never brought in respect of the fire at Bonnington House. The analysis of the diary continues over several pages, but the detective work did not lead to any additional charges. The main witness for the Felixstowe fire was a Commander White of the Royal Navy, who recollected speaking to Hilda and Florence near the hotel. Both women took exception to his evidence, throwing their shoes at the witness box, and shouting so loudly it was hard to hear his testimony. Various witnesses testified to seeing the women in the environs of the hotel, or laughing at the scene of the fire the next morning. Similarly, witnesses testified finding suffragette literature, including labels with slogans on, near both stack fires. The case was adjourned until witnesses from Great Yarmouth could be brought to Felixstowe. The following day, the witnesses, from Great Yarmouth, were questioned. The damage to the pier was estimated at £15000. An eight-year-old boy had found a card at his vantage point, watching the fire, which read ‘McKenna has nearly killed Mrs Pankhurst. We can show no mercy until women are enfranchised’. Hilda shouted out ‘That’s splendid. I wonder whoever wrote that. Isn’t it splendid’. One witness had seen two pictures Hilda had bought of the pier before and after the fire which the police had then found in her possession. Hilda pointed out that there had been eight fires that day so why were they only being charged with one. Both women declined to proffer any defence. The case was sent to the Assizes and bail was denied. On 27 May, the two women were convicted. Hilda was sentenced to two years in Division II. In response, Hilda suggested that the judge ‘put on the black cap and pass sentence of death and not waste breath’. The two women were moved from Ipswich gaol to Holloway Prison on 29 May. Again, Hilda refused food and was forcibly fed. Mary Richardson, a fellow prisoner, wrote to the Suffragette, following her release, that Hilda was ‘very weak’ and was being fed four times a day. She had lost a stone in weight and was sick after each feed. On 6 August, Hilda filed a petition: ‘After a great deal of thought and consideration I have made up my mind that, in future I shall do no more militant work’. It is unclear what prompted her to alter her mind; the impact of weeks and weeks of force feeding or perhaps the advent of war? Two days later Hilda was released. In 1916, Hilda married Leonard Mitchener, a clerk and tutor. The couple, eventually, separated and, by 1939, Hilda is living in St Albans, working as a confectioner and cake maker. Hilda died on 7 March 1955 in Blackpool. In 2014, The Felixstowe Society installed a plaque to commemorate the fire at the Bath Hotel. For more information https://thepeoplespicture.com/hilda-burkitt/ For family photos and a piece by Lauren Hall, her great, great, great niece /thepeoplespicture.com/hilda-burkitt/

0 Comments

|

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed