|

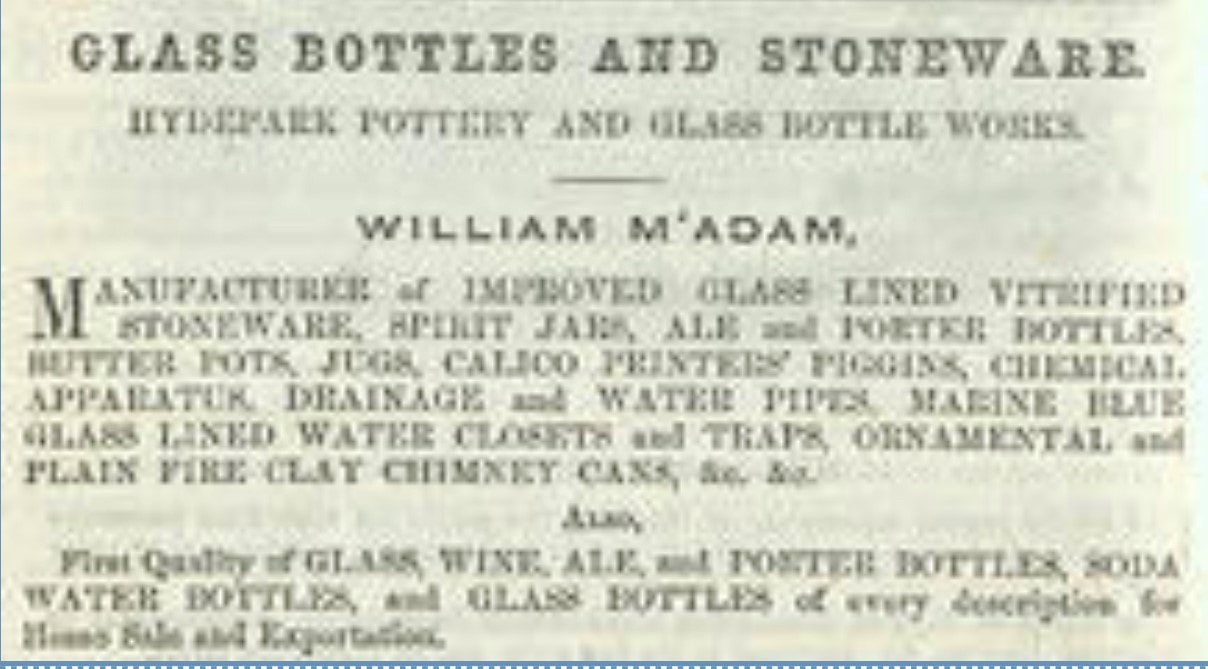

Constance Jane Clyde was arrested in March 1907. She was born Constance Jane McAdam on 25 July 1872, in Glasgow, to William and Mary nee Couper. Constance was the third youngest of twelve children. William was a potter, glass bottle manufacturer and plumbago crucible maker operating from Hyde Park Street while the family home was at 30 St Vincent Crescent. William’s business was called the Hydepark Pottery and Glass Bottle Works. William’s brother John was politically active in Glasgow initially during the early 1830s and the protests connected with the Reform Act of 1832. Three groups dominated Glasgow in the cause for parliamentary reform and John belonged to all of them. John organised a protest on 12 May 1832 known as the Black Flag demonstration, with many carrying flags, often black adorned with symbolic images. Arranged at short notice, it was estimated that over 60,000 gathered. Perhaps because life became difficult for John in the city, he sailed for Canada, living there or in America for the next fourteen years. During his time in America, John became a supporter of Guiseppe Manzzini advocating a united Republican Italy. On his return, he joined William in the Hydepark Pottery. John, in his autobiography, observed that William provided ‘continuous sympathy and active help to the various movements I have been engaged in …has aided me to do some service and to possibly obtain more credit for it than is strictly mine.’ John writes William was an active member of the town council protesting, on one occasion, at the proposal to send a delegation to London to meet with Napoleon. A member of the Water Trust, William lobbied for the passing of the Glasgow Corporation Waterworks Act 1855 which gave the city a supply of clean water. John and William started a fund in 1856 to raise monies to build a monument in memory of William Wallace. When the project looked like it would fail, John rallied additional support and William stepped in to act as treasurer. By the spring of 1879, William’s business ran into financial difficulties. According to his brother, John, this was because of William’s ‘property speculation.’ The following January, the business went bankrupt. William and his brother put many of the assets including 35000 jelly jars up for auction. William resolved to start a new life and sailed with his eleven surviving children and wife to New Zealand. The family settled in Dunedin on South Island’s southeast coast. Despite being in his mid-sixties, William tried to find work writing to the local council citing his experience in the water industry. An offer he remade a few months later, this time to the Ashburton Borough Council enclosing ‘glowing testimonials.’ William sadly died the following year. The family remained in Dunedin. Mary, Constance’s mother signed the New Zealand petition for women to get the vote. After school, Constance began a career as a journalist, moving, in 1898 to Sydney, Australia, to work for the Bulletin, a magazine first published in 1880. As a publication, it developed over time into a showcase for new writers many of whom went on to be authors of national acclaim. Initially, Constance wrote short stories, her first story was called Hypnotised. She wrote poetry reviewed as processing ‘dainty and subtle lines.’As time went on, she explored social issues writing an article about Sydney’s slum life and another about poor relief which concludes: ‘what are they but animals, without the compensations of animals?’ Constance also wrote short stories published in the press in New Zealand. Late in 1903, Constance sailed for England. One newspaper described her as ‘perhaps, the most talented of our Australian writers.’ Members of the Yorick Club, a Bohemian set of artists and writers of Sydney to which Constance belonged, gathered at the studio of Amanduas Fischer to bid her farewell. Constance wrote articles sending them for inclusion in a variety of Australian newspapers. One entitled Is London Civilised contains the initial observations of an Australian in London. Constance questions whether the London policeman is as knowledgeable as claimed given he can only give directions pertaining to his patch. She also wrote a series of articles on working-class life in London for the New Zealand newspaper, Otago Witness. Constance wrote to the Newsletter that while British ‘editors are not sitting waiting on her doorstep’ they were making encouraging noises. Constance found the weather ‘dreadfully depressing,’ and observed ‘this is a slow country.’ While she was making ends meet, the time it took for a decision infuriated Constance who observed ‘no wonder the people live long; they have to in order for any of their ventures come to fruition.’ In 1905, Fisher Unwin published her book A Pagan’s Love which, through a tale of a woman contemplating an affair, challenged social conventions. It met with mixed reviews in Australia. One reviewer, who felt that Constance’s true metier was juvenile fiction, wrote of her book that it ‘deals with the psychology of sex in a manner approaching hysteria.’ Another described it as ‘a daring, but unpleasant novel.’ More positively, the reviewer in the Register described the ‘literary style as excellent.’ The reviews in England were on the whole more positive if lacklustre, the book ‘is entitled to praise if only for the pictures presented of various types of humanity.’ While Constance wrote of life in England for publication in the Australian and New Zealand newspapers; she wrote of colonial life for the English press. In one, titled The Woman Worker in the Colonies, she observed that the law in the colonies for women was ‘more liberal.’ A short story, Two Bush Lovers, was published a few months later, a story of Sydney. Over the next two years, Constance was a regular contributor to the newspapers and magazines in Australia, England and New Zealand. Constance was arrested in March 1907. She wrote an account of her experience published in the Sydney Daily Telegraph. Constance called it ‘a woman’s battle,’ one which was ‘purely physical.’ The policemen in ‘that hysteria to which this class of men are liable, hustled and arrested innocent people who did not even know that a suffrage riot was in progress.’ The English press had only given ‘a mild account of the trampling and confusion that led to the arrest of fifty-seven.’ She wrote of the arrest of mill workers and of Charlotte Despard, who had been ‘left alone by the police in previous riots because of her great popularity.’ This experience, Constance contrasted with a procession the previous week which had passed peacefully with no arrests, observing ‘it is the custom of the suffragettes to give an occasional peaceful demonstration in order to show that their violence is of malice prepense, and not innate.’ She was struck by women such as Lady Frances Balfour or Lady Strachay walking side by side with mill workers and the participation of ‘timid bourgeois daughters’ or ‘prim teachers’ whose bravado in joining in made Constance believe that the vote ‘may really be at hand.’ Constance slipped into the procession just past Hyde Park feeling that ‘for sixty seconds after that the eyes of all London were upon her.’ A favourite cry from the watchers was ‘Go home and do housework’ or ‘What is England coming to?’ One policeman admonished an onlooker for pointing their finger at the woman, but did not question ‘the rude tongue.’ She was fined 20 shillings or 14 days in prison. Describing herself as ‘a shy little novelist’, Constance refused to pay the fine and found herself in prison. The Sydney Daily Telegraph reported it would teach her to have only complained, a few days before, of life being ‘dull and bereft of excitement.’ Constance’s experiences were reported in New Zealand and Australia. Constance wrote she had resolved to show solidarity and ‘admiration for those brave women who chose this method of warfare at a time when all England was against them’ adding that it was a respectable way to gain access to prison suggesting it was her journalistic curiosity that led her to refuse to pay the fine. Prior to her arrest, Constance left Caxton Hall after the normal rally, but being a novice strolled around not knowing what to do. She returned to the hall and sought advice. They advised Constance to rescue a protestor in the clutches of the police. An experienced suffragette explained that a protestor will push and remonstrate until seized and then the ‘amateur’ tells the police to let go of her friend, who probably she has never met before. By dusk, Constance, following the advice, found herself at the police station charged with obstruction. Frederick Pethick Lawrence stood bail for all the women who returned to court the following morning. The women were held in a yard with one bench for seven hours as, one by one, they were brought before the court. The police watching over them, the arrestees claimed, were largely in favour of suffrage, explaining that, in their view, the bringing in of police from the East end of London who did not understand their methods had caused the problem. Constance, in contrast to many, did not mind the journey to Holloway, but objected to being held in a reception cell, three to each one, for three hours with only one chair. Fearful of the consequences of sitting on the floor, the three took turns to walk around the cell for four hours until they were led out for a medical. Clad in prison boots and a loose uniform, Constance did not reach her cell until 2am in the morning, only to be woken by the morning bell three hours later. Cleaning her cell followed morning ablutions and then, breakfast of tea and ‘an excellent wholemeal bread and butter’ – an innovation. More cleaning the cell followed and then chapel and exercise, during which no speaking was permitted. Periodically, the wardress would shout ‘Reverse’ and the line of women would traverse the yard in the opposite direction. Third division prisoners would deliver lunch to the cells in dinner tins. Normal fare was potatoes with pea stew, boiled beef or pork with a roll. The rest of the day was spent in the cell reading, knitting or in contemplation. Constance reported that it was only by the second week that ‘the monotony preys on our spirits’ and ‘physical weariness’ set in. Until 6pm the women had to sit on backless stools. Only then could they lie on their beds. The electric light was good and the cell warm so much so that Constance would stand on her stool to get some fresh air through the grill. After the clocks changed, no light was allowed and as the gloom of the evening descended, the women had several hours when they could not see sufficiently to do any activity. Each cell was equipped with a Bible, hymn book, prayer book and a piece of cardboard attached to which was a morning and evening prayer. A slate and slate pencil was also provided. Constance’s request for pen and paper was denied. The WSPU sent a newspaper in each day. In a wicker basket, once a week, a library was brought round. Periodically the prison doctor, visiting magistrate or the governor would do rounds of the cells. Once a week the women were allowed to bathe. On release, their supporters gave them a tube ticket and another for entry to Eustace Miles restaurant where they had breakfast. At each place lay a bunch of narcissi. It was widely reported that Constance was writing a second novel which ultimately became a play which is discussed further below. She wrote an article, ironically published in the Gentleman magazine, in which she reflected that perhaps women as outsiders ‘feel free to criticise what she has not helped to make.’ Constance continued to write, touching, on occasion, on social problems such as an article on how the living in system affected shop girls. In another she gave her ideas of A Woman’s Utopia. The Women’s Franchise included a poem written by Constance, Fighting On – Suffrage Song, drawing on her experiences of suffrage processions and prison: ‘We have known the prison fastness; we have shared in darker fears; We have stood upon the roadway ‘mid the insults and the jeers.’ In a further edition, Constance argued that an English woman would only make progress if she believed in herself more than she did in men. It was a view that garnered much press coverage and thus publicity for the cause. Such subjects were mixed with articles on how to decorate a home from a penny bazaar or short stories for adults or others aimed at children.

In addition, Constance continued to contribute to the Australian and New Zealand press providing insights into English life particularly aspects which affected women. In one, The English Club Woman, she delivers an exposition of the reason why women joined clubs. Many women writers and artists, including herself, had rejected membership as it was ‘conducive to smoking room loafing, and the mental stagnation that comes with desultory intercourse.’ Constance perceptively portrayed the club ‘habitue’ who made it their job to grumble. Recollecting one dinner she attended, where her host placed a minute piece of meat in an envelope and dispatched it to the committee, Constance observed that it could have positive outcomes. In this instance, the catering was overhauled. Towards the close of 1907, Constance wrote about the current position of the suffrage movement. She felt that the schism, which led to the WFL, had drawn the focus away from the actual campaign but reported that in Scotland the movement flourished with men joining a procession for the first time and the Men’s Suffrage League growing day by day. When the Australian suffragette, Muriel Matters, who famously hired an airship to fly over the Houses of Parliament, a target she missed but nonetheless garnered much publicity, returned to her home country for a lecture tour one campaigner she mentioned was Constance. In 1911, Constance converted to Catholicism at Farm Street Church in Mayfair. She wrote a play, Mr Wilkinson’s Widow, which was performed by members of the Actress’s Franchise League at the Lyceum Theatre in late 1912. In 1912 or 1913 Constance left England and returned to Dunedin, New Zealand. She placed advertisements in the New Zealand press offering inside information to literary writers wishing to engage with London publishers. Perhaps heeding earlier advice, she began to focus on writing stories for children. A year later the Australian newspaper, Table Talk, reported that Constance was living in Christchurch, New Zealand editing the social and women’s columns of the daily Evening News. This role she combined with continuing to write short stories, mainly aimed at children, contributing to pamphlets published by the Australian Catholic Truth Society and writing general articles or reviews. She also collaborated on an adaptation of Alice in Wonderland for the stage. Mary, Constance’s mother, died in 1915. By 1918, Constance had moved to Wellington, New Zealand. Her time with the Evening News had ended when publication was suspended during the First World War. She took up employment at the Richmond Special School for Girls situated in Nelson, but continued to write for the newspapers both in New Zealand, Australia and occasionally England. Her appointment led to an article, Like in a Special School. Throughout the 1920s, Constance continued to write. In 1925, she received extensive press coverage for an article which suggested that New Zealanders ‘are more naïve and untrained than Britons … that they have lost their personal freedom, and submit to a reversion to feudal control.’ It was not warmly received. While a collaboration with Alan Mulgan, a New Zealand journalist, which led to the publication of New Zealand, Country and People, was warmly received. In an article in Smith’s Weekly, 14 April 1928, titled Feminist Journalist, Constance is described as ‘one of the most brilliant and versatile’ journalists. She was by now living in Auckland, New Zealand regularly writing for the Auckland Star for the column called Among Ourselves. Ever the investigative journalist the article noted that to understand the workings of institutes you had to work for them. Constance wrote that she had worked ‘on the staff of a back-ward school, sub-matron of a women’s gaol, an attendant at a mental asylum of 1500 inmates.’ The insights gleaned led her to strongly oppose the enactment of the Child Welfare Act which Constance believed gave ‘too much power over family life.’ Constance believed that the Montessori method of education, which focuses on independence and a child’s natural thirst for knowledge, should support children with difficulties. She took her protest to the New Zealand Parliament in Wellington. When the speaker of the House Representatives read the opening prayer Constance, sat in the visitor’s gallery, and leapt to her feet protesting at the Act, a copy of which she tore up and threw to the floor. As she was ejected, Constance observed that she was now the first woman to speak in the House of Parliament. A member of the Women’s International League of Peace and Freedom Constance was also an ardent anti-vivisectionist. In the summer of 1931, her tenure at the Auckland Star appears to have come to an end after ten years and she moved to Brisbane, Australia. The New Zealand Evening Star, 8 July 1933, announced Constance’s death and a flurry of obituaries appeared in many newspapers. Her death was rapidly refuted by Constance with the words, ‘greatly exaggerated.’ In March 1934, she won a short story competition run by the Auckland Star for The Telephone Bride. A prize she won again in December of the same year. This was the start of more regular contributions to the newspaper. Constance was arrested in April 1935 for telling fortunes for gain or payment as Madam Lavinia. Constance said it was a sideline, using the skills she had acquired in England, to her usual employment as a writer, which she practised to bring hope during the economic depression ‘by kindness, sympathy, and advice and by demonstrating that the only ill in the world was the monetary system. Constance pleaded not guilty. Convicted, she refused to pay the fine and was sent to Boggo Road Prison. Not unsurprisingly, Constance wrote of her experience just as she had done all those years before when sent to Holloway Prison. Constance continued to write short stories which she combined with letters to the newspapers on a diverse range of subjects: a picnic, by definition, did not require a knife and fork which only added to the amount of equipment to pile into the car boot or the manners which should be observed when listening to the radio. Often the letters were signed Constance McAdam rather than Clyde. The last publication, I can find, is a sad poem published in the Queensland Times in March 1944. The women who went to prison twice and wrote and wrote for so many years slipped into oblivion. She died in 1951 and no newspapers appear to have carried an obituary. Constance’s extensive observations of life in England as published in the Australian and New Zealand press deserve reconsideration for the insight they give into life at the time. Her writing of her experiences as a suffragette gives a rare detailed view of protest and imprisonment. Often outspoken in her writing she was not afraid to tackle hitherto taboo subjects and cast a light on topics in a thought-provoking manner. As one writer commented ‘her versatility borders on the remarkable.’

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed